PBS's new series Sid the Science Kid stars an inquisitive boy with a knack for asking revealing questions; a companion science curriculum, offered in English and Spanish, helps teachers engage kids and build the skills the show's characters exhibit.

Here’s a way to make the kids’ eyes glaze over: Tell them they have to watch an educational science program on TV.

But plenty of children — and adults — have made science-based shows like MythBusters into hits. Turns out there is a place for TV in science education.

And there’s a need, too: The «hard truth,» as President Obama recently said, is that Americans have «been losing ground» when it comes to math and science education.

«One assessment shows American 15-year-olds now rank 21st in science and 25th in math when compared to their peers around the world,» Obama said.

The president was speaking at the recent launch of Educate To Innovate, a nationwide effort to move the U.S. «to the top in science and math education in the next decade.»

Prominent scientists from NASA and the National Science Foundation were invited to the White House event. So were a couple of cable TV stars: MythBusters creators Adam Savage and Jamie Hyneman.

Everybody loves science when he or she is young. You cannot find a kid that doesn’t want to taste the kitchen floor.

‘Science Guy’ Bill Nye

«I hope you guys left the explosives at home,» Obama joked. And not without cause: The MythBusters love to blow stuff up.

It’s not a science show per se, but scientists are some of its biggest fans. Since launching the series eight years ago, Savage and Hyneman have been inducted into Sigma Xi, the Scientific Research Society. The California Science Teachers Association made them honorary members. They’ve been asked to speak at numerous schools, including MIT and Georgia Tech. Savage says they get the rock-star treatment when they visit.

Recent episodes of MythBusters include «Can a sonic shock wave shatter glass?» and «Does double dipping cause germ warfare?» They go to great lengths to get to the bottom of these popular beliefs.

And their experiments are highly dramatic. In one episode, Savage and Hyneman visited the world’s largest portable hurricane simulator — nicknamed Medusa — at the University of Florida to test whether it’s better to keep the windows of a house open or closed during a hurricane.

Savage and Hyneman are quick to point out that they are not scientists — in fact they’re former Hollywood special-effects guys — and they didn’t create the show to educate.

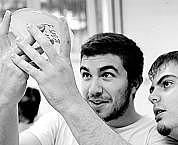

MythBusters: Jamie Hyneman and Adam Savage (with Buster the crash-test dummy) put science to work week in and week out on their Discovery show.

«We don’t have pretensions to be teaching,» says Savage. «We’re still very much in touch with the 14-year-old pyromaniacs inside us.»

But high-school science teachers approve. Mindy Bedrossian, of Strongsville, Ohio, says her students turned her on to MythBusters, and she thinks what the guys do on the show is «raw science at its best.» She even wants her students to test hypotheses the way they do on MythBusters: They study. They measure. They build high-tech props. They test — over and over again.

«We don’t want [students] to blow up buildings and things like that,» Bedrossian laughs. «But we would like for them to do science in exactly the same way.»

Bedrossian says she pays close attention to what science TV shows are out there. She’s concluded there’s a lot of garbage. But her real problem is that schools themselves are offering so little science education in the younger grades.

That’s where TV can help. There are a number of new science shows aimed at the very young:Dinosaur Train, Zula Patrol and Sid the Science Kid. The latter premiered on PBS last year, partly because Linda Simensky, the head of programming, was frustrated there weren’t many science shows for the pre-school set. So she commissioned the Jim Henson Company to create one.

«I really wanted daily science that you encounter every day in life,» says Simensky. «And something that models asking questions.»

Sid asks plenty of questions. In fact Sid can be — how to put this nicely? — a little annoying. He’s an extremely happy extrovert who loves his toy microphone, and who’s hugely curious about how stuff works.

Will the show actually impart any knowledge to little viewers? The producers aren’t making any guarantees. But they do hope Sid will get kids excited about science.

According to Bill Nye, that shouldn’t be too hard. Nye stopped producing his show Bill Nye The Science Guy in the late 1990s, but teachers around the country still show it to their students.

«Everybody loves science when he or she is young,» says Nye. «You cannot find a kid that doesn’t want to taste the kitchen floor, or that doesn’t want to know how houseflies make a living.»

He says the U.S. needs young scientists — so why not start with this willing audience?

Artículo original en: http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=121146862

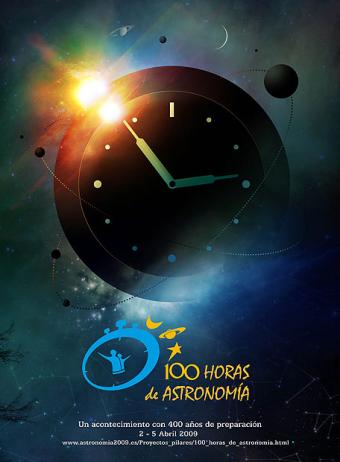

La Real Sociedad Española de Física, tiene la satisfacción de enviar esta primera circular anunciando la XXI Olimpiada Española de Física, cuya Fase Nacional se celebrará en Alicante del 8 al 11 de abril de 2010, con el patrocinio de la Universidad de Alicante.

La Real Sociedad Española de Física, tiene la satisfacción de enviar esta primera circular anunciando la XXI Olimpiada Española de Física, cuya Fase Nacional se celebrará en Alicante del 8 al 11 de abril de 2010, con el patrocinio de la Universidad de Alicante.

Cuatro de los alumnos probando ayer en el exterior de la Facultad de Ciencias las ópticas de sus telescopios.

Cuatro de los alumnos probando ayer en el exterior de la Facultad de Ciencias las ópticas de sus telescopios.

Ángel Biarge, en pleno proceso de pulido, junto a dos participantes en el curso.

Ángel Biarge, en pleno proceso de pulido, junto a dos participantes en el curso.

Cómo medir el radio de la Tierra con un recogedor

Cómo medir el radio de la Tierra con un recogedor Con la ayuda de los profesores, los alumnos participarán en una adaptación de este método. Para ello deberán situar en algún lugar plano y con buen Sol, un gnomon, es decir, un palo, una vara o un simple recogedor de polvo, y registrar la evolución de su sombra durante varias horas a lo largo de la mañana. Este registro permitirá a los alumnos obtener el primer dato necesario para participar en el proyecto: la altura del Sol en el momento del paso por el meridiano.

Con la ayuda de los profesores, los alumnos participarán en una adaptación de este método. Para ello deberán situar en algún lugar plano y con buen Sol, un gnomon, es decir, un palo, una vara o un simple recogedor de polvo, y registrar la evolución de su sombra durante varias horas a lo largo de la mañana. Este registro permitirá a los alumnos obtener el primer dato necesario para participar en el proyecto: la altura del Sol en el momento del paso por el meridiano. Inauguración Lunes 6 de abril a las 9:30 horas en la Sala de Grados de la Facultad de Ciencias de la Universidad de Oviedo

Inauguración Lunes 6 de abril a las 9:30 horas en la Sala de Grados de la Facultad de Ciencias de la Universidad de Oviedo